Most Czechs and Slovaks do not use AI, but fear of deepfake scams is growing

While artificial intelligence-generated content is becoming a common feature of the digital landscape, a majority of the population in the Czech Republic and Slovakia does not consciously or actively use these tools. According to a new study by the Central European Digital Media Observatory (CEDMO), 62% of Czechs and 57% of Slovaks have no practical experience with tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, or Midjourney. Despite this, concern is growing in both countries about their potential for misuse, particularly in the form of deepfake videos, which are increasingly being used to spread disinformation, for politically motivated attacks, and in financial fraud.

The study, conducted by Prague's Charles University in cooperation with the polling agencies Median and Ipsos, highlights a contrast between the media portrayal of a massive AI boom and the reality of its everyday application. Some 38% of Czechs and 43% of Slovaks admit to having tried generative AI at least once. However, only a small fraction of the population uses these technologies daily – 7% in the Czech Republic and 11% in Slovakia.

AI adoption is strongly linked to age. Young people aged 16 to 24, primarily students, are the most active users. In this age group, approximately a quarter of Czechs and nearly a third of Slovaks use AI on a daily basis. Usage then drops sharply with the age of the respondents. Despite the relatively low numbers, there is a clear year-on-year increase. While 74% of Czechs reported no experience with AI in 2024, that figure has fallen by 12 percentage points this year. In Slovakia, the number of non-users decreased by 7 percentage points.

The survey also showed that even those who use generative AI approach it with a high degree of caution, with the vast majority aware of the risk of inaccuracies and factual errors. „Most users declare a wary approach to generative AI tools. More than half (53%) of Czech and three-fifths (60%) of Slovak users state that they tend to trust the outputs but also verify them from other information sources,“ explains CEDMO sociologist and data analyst Ivan Ruta Cuker. The most common tool for verification, he notes, is an internet search engine, used by 82% of users in the Czech Republic and 73% in Slovakia. Verifying information in professional literature or consulting with others follows at a significant distance. Only 4% of Czech and 6% of Slovak users trust AI completely, without further checking the generated outputs.

In Slovakia, trust in AI varies by gender, age, and political preference. „Women (9%) are significantly more likely than the general population and men (4%) to completely trust answers generated by artificial intelligence. A higher level of complete trust is also observed in the 16 to 24 age group (12%) and among the part of the population that is satisfied with the functioning of democracy in Slovakia (15%),“ explains sociologist Paula Ivanková from Ipsos. „People aged 35 to 44 tend to trust AI outputs but are more likely to verify them from other sources (68%). Conversely, older cohorts aged 55 to 64 and people with university education were more likely to state that they tend not to trust the outputs and use them with reservations. The highest level of distrust was expressed by voters of the Smer-SD party. Up to 43% of them stated that they tend not to trust AI-generated answers, which is higher than the figure of just under a third for the entire population,“ Ivanková adds.

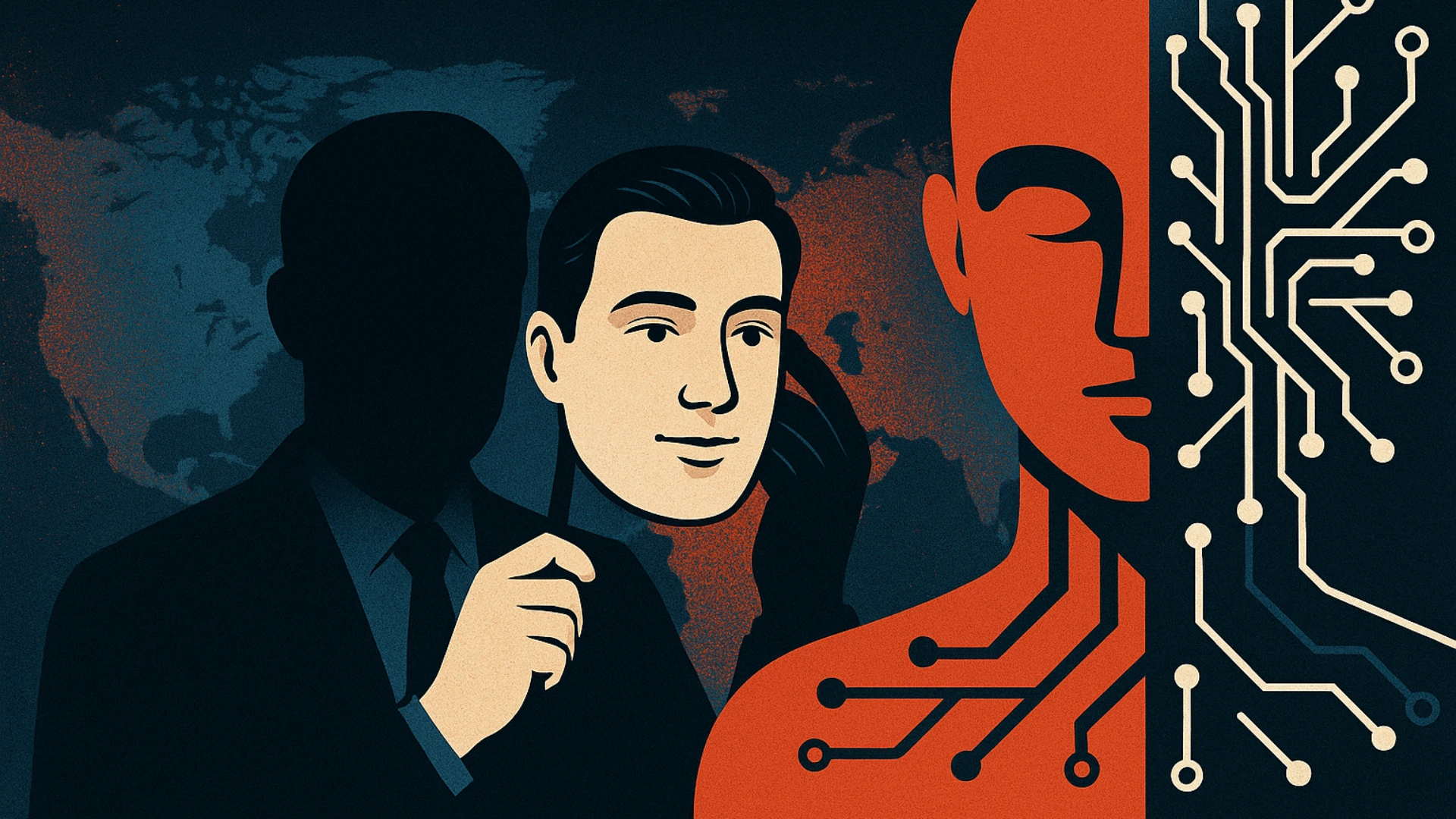

While ordinary users are still discovering the possibilities of AI, purveyors of disinformation and fraudsters are already fully exploiting the ability to clone the appearance and voice of well-known personalities. The phenomenon of deepfakes – realistic but entirely false video or audio recordings – is becoming more frequent. Approximately one-third of Czechs (32-36%) and two-fifths of Slovaks admit to having encountered them.

In the Czech Republic, scams have included videos featuring well-known doctors, such as surgeon Pavel Pafko, offering „miracle“ cures, and fake investment advice from politicians promoted on pages mimicking the websites of major news broadcasters like CNN Prima News. Other deepfakes have falsely depicted epidemiologist Roman Prymula warning against Covid-19 vaccination. Disinformation targeting Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has also circulated, including a fake news report, believed to be part of a Russian influence operation, alleging he bought a stake in a South African mining company.

The situation is similar in Slovakia, where disinformation campaigns are often repeated. For instance, AI-generated videos purporting to show President Zelenskyy under the influence of drugs have circulated, with one reaching two million views. An AI-generated image intended to „prove“ that Olympic boxing champion Imane Khelif was male was also spread, identifiable as a fake by details like distorted features in the background.

The proliferation of deepfakes is causing strong public concern. After viewing specific examples during the research, an overwhelming majority of respondents (77-86% in the Czech Republic) expressed fear that deepfakes will significantly increase the amount of disinformation. This has led to a strong demand for regulation, with most Czechs (85%) and Slovaks (76%) agreeing that AI systems must respect user privacy. A large portion of the population in both countries also supports making social media operators and internet platforms responsible for deleting deepfake videos.

Czech police report victims of „investment“ fraud almost weekly, with damages often reaching millions of crowns as people lose not only their savings but also take out loans or sell property. In one case, a man lost nearly three million crowns (approximately 120,000 EUR) after being lured by a fake post from a well-known politician. Broadcasters like ČT24 and CNN Prima News are attempting to combat the misuse of their brand and presenters' likenesses by reporting fraudulent videos and issuing warnings, but they have few other options to counter the wave of manipulated content.